This study focuses on the era of interwar modernism in Košice: functionalism, rationalism, Bauhaus, Art Deco, Rondo Cubism, neo-historicism, national romanticism, etc. We are trying to reduce this into two main competing tracks: the architecture of the future and promotion of national expression and to identify a purely local identity in this. Lajos Oelschläger was a prominent exponent of this idea – the “natural and elegant incorporation of a new architecture into the historical surrounding.” The external unbiased view allows us to impartially examine the modernist architecture of this period for its uniqueness, emphasizing the importance of local tradition in the post-imperial environment. It is an attempt to see how regional and cosmopolitan approaches to art and architecture overlapped and influenced each other. Košice's architectural and artistic plurality of that period strikes and intrigues the most.

Art

In the 1920s, interwar Košice, part of newly-formed Czechoslovakia, became a vibrant centre of cultural life. However, it took a rather long to explore the regional vibe through the lens of the global modernist movement, going beyond the centre / periphery dualism and challenging traditional hierarchies. The domestic context of the 1920s and 1930s can be viewed as the transgression of all local boundaries, “ambitiously measuring itself against Europe and the world.”

According to art theoretician Matthew Rampley (Networks, Horizons,Centres and Hierarchies: On the Challenges of Writing on Modernism in Central Europe), studies of the avant-garde revised the geography of art, which historical framework traditionally focused on such centres of modernism as Paris, Berlin, New York, and London. The modernist art world of East-Central Europe before 1918, dominated by the old imperial capital, gave way to new sites – Zagreb, Brno, Salzburg, Poznań and Košice. By mapping the movement of avant-garde artists and the circulation of their works in the 1920s, we could trace that historical ties between ‘peripheral’ centres and capital cities lost their dominance, and new networks were established.

Michał Burdziński, an expert in comparative studies investigating the history of modernist art in Central Europe, defined the Slovak context as “a multicultural existence, fundamentally friendly, based on a dialectic of explicitly Slovak elements and Czech, Hungarian, German and Ruthenian elements that have coexisted on the territory of the present republic, not always in harmony, for several centuries.” Further, he mentions numerous monographs and specialised catalogues that explored a new face of local culture and its dual status: Slovak and, at the same time, Central European (Young Slovakia. About the Meanders of Modern Art Between Žilina and Košice).

The art historian Hans Belting stated that a more promising critique draws attention to networks and the mobility of art and artists, many of who were associated with the Budapest, Vienna, or Berlin environments.

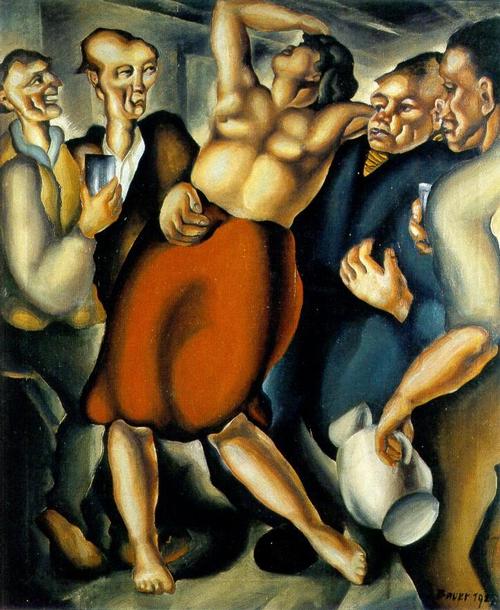

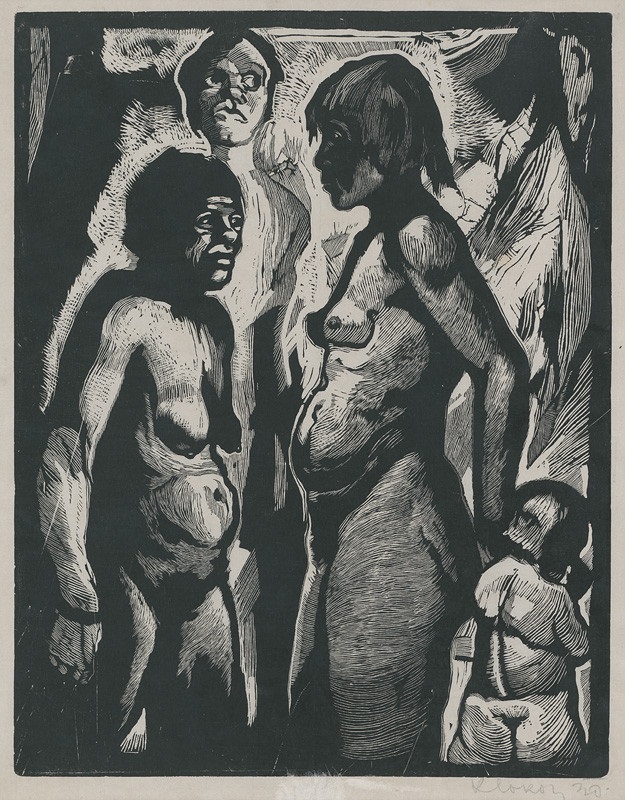

Condemned, Konštantín Bauer (1927)

All this is critically important for understanding the phenomenon of Košice Modernism, a term coined by curator Zsófia Kiss-Szemán, and referring to the cultural upsurge in the 1920s Košice. Artists from various parts of the former monarchy worked here, reflecting on turbulent reality and contributing their diverse visions to the current social-critical discourse.

In 2016, Zsófia Kiss-Szemán curated the exhibition “Koszycka moderna/Košice Modernism” in cooperation with the East Slovak Gallery, presenting the bilingual catalogue “Košice Modernism” that introduced its prominent representatives: Sándor Bortnyik, Anton Jasusch, Eugen Krón, František Foltýn, Géjza Schiller, Koloman Sokol, Konštantín Bauer, with the completist analysis of the phenomenon so far. Earlier, it was the core of the exhibition “Košická moderna a je presahy” within the Košická moderna project, hosted by the East Slovak Gallery in 2013, when Košice was the European Capital of Culture and curated by Zuzana Bartošová and Lena Lešková.

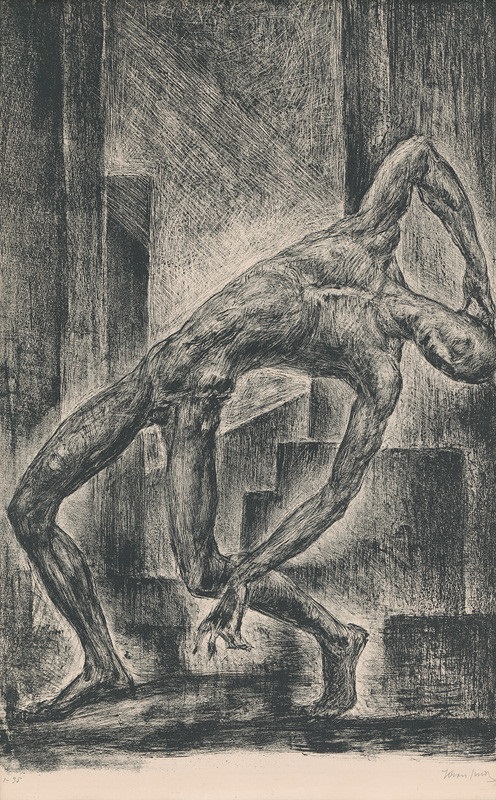

Falling, Eugen Krón (1927)

Graphic artist Eugen Kron studied at the Lithographic Institute and the Academy of Fine Arts in Budapest, and in 1919 emigrated to Košice with the intention of reaching Germany. On the initiative of Dr. J. Polak, Kron stayed in the city for 6 years and founded a private school of drawing and graphics. His graphic cycles Man, Creative Spirit and Man of the Sun give a clear idea of his work at that time, and it was the most fruitful period in his life. He also created views of architectural monuments in Košice.

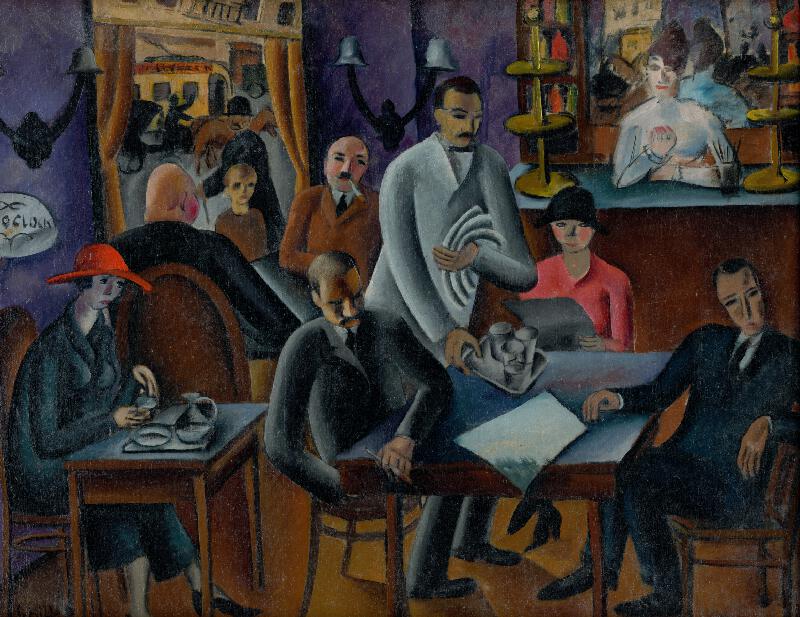

Košice Modernism did not stay aside from the modern urbanism tendencies, drawing inspiration from the slow but crucial changes in the city landscape. The modernist urban motifs manifested in depicting café routine, public and private life, industrial boom – all the signs of inexorably advancing progress.

In the cafeteria, Gejza Schiller (1924)

As well as a dark side of the progress – social tension, poverty, and crisis that resonated in the work of some artists (Unemployed, František Foltýn, 1924).

Unemployed, František Foltýn (1924)

Although the new lifestyle conquered Košice not so fast as big cities, its obvious manifestations – electricity masts, phone lines and factory chimneys, and other “innovative” alterations of the urban landscape – can be found in many works of that time, especially those by Konštantín Bauer who was evidently inspired by European Expressionism.

Košice in spring, Konštantín Bauer (1927)

I cannot but mention Dr. Josef Polak and his pivotal role in developing an institutional framework of Košice modernity. He became the director of the East Slovak Museum in 1919, contributing tremendously to the ambition of the institution to gain a reputation as the most versatile Slovak gallery centre. It was he who invited artists to stay in the city and created conditions for their work. His portrait by Sándor Bortnyik, a representative of Hungarian Constructivism, is an homage to both de Chirico’s metaphysical painting and Polak’s modernity.

Portrait of Dr. J. Polák, Sandor Bortnyik (1924)

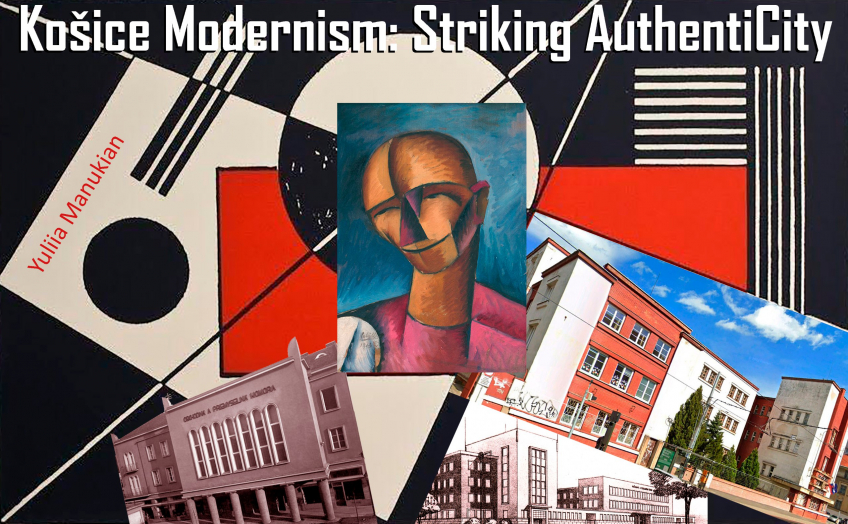

My admiration with Bortnyik was a reason I had chosen his Composition (1921) for the background of the presentation collage. The Cubistic “Head of a Man” by Gejza Schiller (1923), another prominent representative of Košice Modernism, was ideally installed in the Composition’s geometry. It organically “appropriated” the iconic Chamber of Commerce and Industry by Ľudovít Oelschläger, the modernist complex of the Post and Telegraph Office by Bohumír Kozák and the purist State Secondary Grammar School for Girls by Petr Kropáček.

The Head of a Man, Gejza Schiller (1923)

The Hungarian Gejza Schiller and the Czech František Foltýn were both nomad artists and friends who integrated their experiments into the local art scene for a year.

Schiller, like Bortnyik, emigrated after the defeat of the Hungarian Republic. Fascinated by Košice, he created many cityscapes. In 1924, the artist went to Transylvania, where he devoted himself to literary and theoretical activities until his death in 1927. Incidentally, in 1922, he and Foltýn exhibited in Uzhhorod. Schiller was greatly influenced by the work of Der Blaue Reiter, which he studied in Berlin.

Townscape, Gejza Schiller (1924)

František Foltyn also survived the First World War, after which he settled in Košice. In the mid-1920s, he moved to Paris, where he joined the Cercle et Carré group, which focused mainly on geometric abstraction. In 1934, he settled permanently in Brno. Foltyn's artistic work can be divided into three periods, according to the places he lived, which were influenced mainly by the Cubist and Expressionist movements. During his stay in Slovakia, he often travelled to Subcarpathian Rus, which fascinated him with its landscapes. Among his most famous works of that time is Gypsy Quarter (Košice).

Gypsy Quarter (Košice), František Foltyn (1922)

Konštantín Kővári-Kačmarik and Julius Jakoby were the ones most dedicated to the city’s topography in all senses.

Kővári-Kačmarik depicted city streets, corners, and courtyards in a manner that represented a bridge between Art Nouveau and Symbolism, having an essential impact on the further development of Slovak Modernism: "Much greater formal innovations and a remarkable courage in building perspective exclusively through paint spots – flat and synthetic Gauguin style, or bold and impasto van Gogh style – characterise the work of Konštantín Kővári-Kačmarik, pioneer and spiritual patron of the interwar achievements of the Košice Modernists. The artist died in a psychiatric clinic in 1916 aged 34, but his canvases, full of saturated purples, yellows and greens, as well as watercolours, ink drawings, linoleum prints and original pastels, painted on rough cardboard with a soaked and removed top surface, must be included among the best achievements of the fin de siècle in Slovakia" (Michał Burdziński).

View of Rozalia near Košice, Konštantín Kővári-Kačmarik (1914)

Jakoby, the Košice loner, evolved from “undisguised painterly hedonism to a radical minimisation of the configuring elements of the painting. He and Koloman Sokol were members of Eugen Krón’s art school in Košice.

At the bar, Július Jakoby (1929)

Here was the crucial transformation of Anton Jasusch’s worldview. According to Zsófia Kiss-Szemán, in the 1920–1924s, he created his own cosmogony, based on avant-garde utopias – “concerning existential questions of man, the meaning of life and a man’s place on Earth and also in the Universe.”

Free Composition III (Planet Extinction), Anton Jasusch, East Slovak Gallery (1924)

He channelled his war trauma into intensely dynamic and almost futuristic compositions inspired by the art group Les Nabis, remaining absolutely inimitable.

Radium (Composition IV.), Anton Jasusch (1922–1924)

Koloman Sokol is considered the founder of contemporary Slovak graphic art. He studied at the private school of Eugen Kron in Košice, and later in Bratislava and Prague. It was there that he decided on his national identity: "Prague helped me realise that I was a Slovak, not a Magyar."

Mothers, Koloman Sokol (1930)

Sokol was most influenced by van Gogh, Kate Kollwitz, Georg Gross and the Die Brücke. The artist often depicted suffering and human pain, and researchers argued that he "created a Slovak variation of expressionism on a European level."

Thus, it was not a coherent group but of artists with diverse methods and visions. At the same time, it seems to be a man’s club, as female artists have never mentioned in the above studies, remained invisible through the patriarchal perception of the right to artistic self-expression.

Also, I was impressed by the conceptual rethinking of the Modernism collection during the national lockdown at the beginning of 2021. The team of the East Slovak Gallery elaborated the virtual exhibition AR Košice Modernism via the mobile app that enabled people to uncover essential works from the collections connected with art events in the period of the 20s and 30s.

The trick is that five AR markers were placed in the public space of the centre of Košice, but never on Hlavná Street, for people to discover even long-forgotten corners. Such an innovative and insight-offering approach is one of the most efficient ways of promoting of cultural heritage.

More details are available on the Gallery’s website https://vsg.sk/ar/

Photo: courtesy webumenia.sk

Architecture

Our task is to understand the specificity of the architectural and artistic palette of Košice in the era of interwar modernism. In 1918–1920, Košice became part of the newly formed state of Czechoslovakia. At that time, two trends in architecture were gaining popularity in European architecture: the first being international modernism, i.e. modern architecture, or rather the architecture of the future, functional, comfortable, and subordinated to the needs of the individual, which was placed at the centre of the concept of "new life". The second area is the architecture of the identity of the newly formed states, where we focus on identifying specific features for each of them.

The complexity of the approach was the need to combine the features of identity with the emphasis on the nation's aspirations for the future as part of the promotion of the development of new nation-states. This symbiosis resulted in experiments that shaped the unique face of the cities, each of which had a complicated thousand-year history of forming a multinational symbiosis of external influences and local traditions.

The well-known fact is that new city planning has always depended on a new political situation, normally denying the previous developments. The “Roaring 20s” of the twentieth century was not an exception.

At the beginning of the 1st Czechoslovakia, there was created a regulation plan, still “monarchical” but unfinished in any way, giving way to the elaboration of the functionalist plan, the implementation of which became utopian due to the collapse of Czechoslovakia. “The preparation of the progressive plan immediately after the war was disrupted by the onset of the new socialist aesthetic, and the next plan, prepared this time in the spirit of socialist realism, was not completed precisely because of its fall and the return of modern urbanism” (The Urban Planning of Košice and the Development of a 20th Century Avenue, Adriana Priatková, Ján Sekan, Máté Tamáska).

Thus, Košice has a three-city face: the historical burger incarnation during the Habsburg period, the period of transformation of the city into a modern one in the interwar period, and then the socialist industrial city.

Košice "re-thought" the fortress walls quite early, in the 1840s. The development plan of the western glacis was created as part of the city plan prepared by the engineer Jozef Otto, which proposed a grand city avenue with representative public buildings, the modern Moyzesova Street, a realized fragment of the planned ring road around the old city.

Two projects – 1912 and 1938 – present two concepts that differ not only chronologically, but also theoretically. The first one is scenic planning, subordinated to the relief and gentle expansion of the city along the Hornad River in both directions, as well as the inclusion of the river into the structure of the city and new planning districts. It was designed by László Warga and Jenő Lechner (the winners of the very first urbanistic tender in Hungary) in accordance with Camillo Sitte’s principles: a beautiful city with picturesque public areas, plenty of greenery, ring roads, as well as significant industrial complexes, public institutions, an elevated railway, and a river port. The second concept by Josef Chochol is more geometrized, subject to the development of industry and transport networks linking plants, residential areas, and transits. It denied the ideals of Sitte's aesthetics – no picturesque streets or squares, instead of the river port, there was designed an airport. This concept envisaged a linear growth of the city along the river, as opposed to the vision of the city expanding in the centre. It was no longer a visionary plan, but the realistic one that looked ahead 50 years. Thus, there was a shift away from a human-oriented scale to the functional solution of settlement structures.

From the next hundred years of development of urban planning, we can see the return trends of the first concept – the necessity of restricting traffic in the city centre, returning the river to the city structure, and prioritizing the development of its banks with elite housing with the simultaneous formation of a green belt.

From the perspective of our architectural and artistic research, the comparison of these two urban planning concepts will also reflect the directions of architectural trends.

A comparison of the project of 1912 and the real plan of Košice in 1921 shows the crisis of development.

If we return to the centre / periphery dualism paradigm and its contemporary analysis, curious is the fact of the close ties of Le Corbusier with the Czechoslovak intellectual milieu in the late 1920s. He organized a number of events under the name of the Purism and Architecture series in Prague and Zlín, attended by Gropius and Loos. That was the time of the polemics between Le Corbusier and Karel Teige (Czech avant-garde artist and critic) on the Mundaneum project. The sharp difference in their aesthetic doctrines is quite illustrative in regard to that period: Le Corbusier promoted architecture as specialized politically independent knowledge, and Teige, opposing the idea of monumentality of architecture, believed it to be an instrument for revolutionary changes. Besides, Teige was the leading Czech expert on the Bauhaus, writing regularly on it for the architecture-focused magazine Stavba in 1924–1930.

What was the place of Slovak architecture in those radical aesthetic shifts? Since 1918 many Czech architects came to the Slovak part of the republic to develop state infrastructure, bringing Czech cubism. Then came the times of ruling modernist tendencies from France and Germany. The new aesthetics labelled “Bauhaus style” was quickly adopted by the emerging consumer societies – the upraised middle class demanded modernist villas, apartment houses, banks, and department stores, many of which acquired the status of icons.

Ľudovít (Lajos Őry) Oelschläger deserves a separate mention as an iconic figure in terms of the local architectural uniqueness. We know about his legacy so much now thanks to its dedicated researcher, architect Adriana Priatková who together with her colleague Peter Pásztor, members of the Department of Architecture at the Faculty of Arts of the Košice University of Technology, prepared a 344-page trilingual (Slovak, Hungarian and English) monograph collecting materials during 8 years. It was published in 2013 and includes completed and unrealised projects in Slovakia, Ukraine, and Hungary. Őry was one of the 4 personalities of the city who were especially honoured within the European Capital of Culture Programme. In 2012 Adriana Priatková and her team created a travelling exhibition, which visited many cities in Slovakia, Miskolc in Hungary, as well as Uzhhorod, Mukachevo, and Berehove.

The Masaryk Colony for Bank Officials by Josef Polášek (1926–1932)

The Masaryk Colony represents the concept of future life, not only in ultra-modern architecture but also in technology.

Josef Polášek, the architect from Brno, explored the problem of minimal housing criticising the contradiction between luxury housing for the upper classes and emergency housing in labour colonies. In the Masaryk colony, the architect applied the principles of collective housing, where the role of the welfare state begins to be realised. The three-winged block of four-storey buildings was built by a co-operative consisting of 48 families of officials of Czech, Slovak, and Hungarian banks in Košice. The architect promoted the typification and standardisation of building components, which made the whole structure cheaper. Standardized closets for clothes and linens, central heating, and cold and hot water supply were built into the apartments, a common laundry was provided in the residential blocks, green terraces for relaxation on the roof, a children's playground with a swimming pool and kindergartens in the closed courtyard. The aesthetics of the facades followed the one of the New Objectivity Architecture.

We chose this 1926 project to present a concept devoid of any artistic stylizations, nothing but functionality. Although such a house could have been built in any country in the world, and now it no longer looks original, at that time its main idea was to demonstrate a future world, a world of light, health, and technological development. At that time, it was outside the city, in a green zone, and did not interfere in any way with the urban architectural environment.

The Taliya Professional Entrepreneurship School and Theatre by Eduard Žáček (1933)

Later, the eastern part of the building was extended. Since 1969, the assembly hall has been used by the Hungarian theatre.

This is an example of modern architecture in the middle of the city: an educational institution with a theatre. Despite the lack of any decoration, the facade of the building, which closes the perspective of the narrow Pribinova street in the centre of the city, is sufficiently saturated with small details: horizontal balconies and a glazed loggia of the second floor, small window frames harmonize with the general visual smallness of the surrounding buildings (although in this corner today the construction around is also modernist).

The Outdoor Swimming Pool by Ľudovít Oelschläger (1935)

One of the most functionalist objects of interwar modernism is the outdoor swimming pool – pure geometry, advertising a style that did not become popular in Košice at that time.

Ignac Roth Department Store by Ľudovít Oelschläger (1938)

The owners of trading houses and department stores tried to advertise the modern, newest products in Europe in their architecture. Unfortunately, this facade has been changed with the loss of an impeccable compositional solution of planes and slots, verticals, and horizontals.

The Slovak General Insurance Company by Alexander Skutecký (1937–1939)

We attributed this building to the international style. However, as we can see it has a specific influence of Czech cubism: classical articulation on the base and cornice, and columnar panels with windows on the second floor. It is a relatively late building, erected in the year of the beginning of the Second World War, and a certain tendency to bring modernist architecture closer to local traditions can be observed.

The Vocational Entrepreneurial Boarding School named after Dr. Jan Ruman (1926–1927)

Construction: Košice civil engineer and designer Alojz Novák

Now this is the Secondary Industrial School of Construction and Geodesy. Cultural heritage monument No. 3662/0 "Boarding School". In fact, the building of the boarding school is not modernist. But it is a classic example of Rondocubism, which we will rely on in further examples.

The District Court, 1878

Modernized by Adolf Liebscher in 1926

Construction: Alojz Novák

Now the building hosts the Technical University and the Scientific Library. By the way, Adolf Liebscher was a famous urbanist who developed the master plan and concept for the development of Uzhhorod.

There are many objects in Košice that could be attributed to the Czechoslovak Rondocubism style, but we will single out examples of its greatest adaptability to functionalism. The district court building of 1878 was rebuilt in 1926 precisely with the aim of not only modernizing it but also emphasizing state affiliation. In fact, it is also far from pure modernism, however, it is an important example to illustrate a certain competition in the identity of Košice.

The rental house by Ľudovít Oelschläger, Fejova 3 (1936–1937)

Construction: Brothers Wirtschafter (Kosice), engineer Hugo Kaboš

It is a bright example of the combination of Rodocubism and functionalism on a local basis.

The Masaryk Social House by Rudolf Brebt (1928)

In the 2000s – the building XV of the University Hospital named after. L. Pasteur.

Cultural heritage monument No. 4119/13 "PAVILÓN NEMOCNIČNÝ", part of the complex of monuments "NEMOCNICA S AREÁLOM".

The sculptures on the façade appeared in the 2nd half of the XX c.

Extension: architect František Faulhammer (1936–1938)

Reconstruction: 2010

One of the buildings of the large complex of the Pasteur Hospital, which is generally designed in a modernized folk style (Heimatkunst) with the influence of Rondocubism. This corpus, built by Rudolf Brebt and expanded by František Faulhammer, is distinguished from the others by the greatest influence of functionalism. At the same time, it carries the clear Czechoslovak identity formed in those times just as strongly.

The Reform (Neolog) Synagogue, later ‘The House of Art’ by Lajos Kozma (1924–1929)

Extension in 1953

The building of the Neolog Synagogue is chosen as the title photo of the following topic: the search for Hungarian identity in functionalism. Oddly enough, several buildings erected for the Jewish community of Košice were included in this section. Obviously, in search of certain features of the deep roots of both cultures, the architects came to an important unifying element – a narrow semicircular arch and a set of stylized elements and forms characteristic of Hungarian rationalistic neo-baroque. The ornamented dome is the most striking element in the building of the Neolog Synagogue.

UZPF number 3372/1

Administrative building (1920–1930)

Address: Drevny Torg, 3

The Chamber of Commerce and Industry by Ľudovít Oelschläger (1929–1933)

Reconstruction: engineer-architect Ladislav Štofko (1958)

Ľudovít Oelschläger was a sincere adept of the Hungarian influence on modernist thinking. The presented the following four buildings, in our opinion, fully correspond to the determined stylistic direction. First of all, the building of the Chamber of Commerce and Industry, which for entrepreneurs from other cities and countries, should demonstrate the most expressive local architectural modern style at that time.

The Fire Station by Ľudovít Oelschläger in cooperation with Gejza Zoltán Boskó (1925–1927)

This is precisely the task – to present the key features of the city's identity through modernity – Oelschläger set himself in the building of the Fire Station. The complex of buildings of the Fire Station, which are interconnected with volumes of small “bridges”, is situated in the quiet residential area to the southeast of the Urban Conservation Area border. Oelschläger created interesting and dynamic urban premises by forming the façades, shifting the bodies of the buildings, and using different heights of the floors. The compact, refined architectural volumes of all three Fire Station buildings with original morphological elements became the natural dominant feature of the area. Since its opening in 1928, the Košice Fire Station has functioned without any essential alterations.

The Orthodox Synagogue and the Jewish School by Ľudovít Oelschläger (1926–1933)

Construction: Hugo Kaboš

In the buildings of the Synagogue and the Jewish school, Oelschläger added, of course, some stylizations of the Jewish identity, based on the modern reinterpretation of the architectural studies of the Temple of Solomon on the Temple Mount in Jerusalem.

The Synagogue along with a school and a ritual bath was initially an enclosed complex. Facades oriented to the street were intertwined with a stylized arcade. Although the drawings of all the buildings were finished at the same time, the synagogue was built earlier than the school. The project bears the characteristics of the architect‘s early years, where a sort of rondo-cubist style merges with historical themes, in this case, Renaissance architecture. The synagogue is based on an elongated symmetric layout, with the main prayer hall being lined with a gallery. A two-storey school wing has a simple two-aisle floor plan, initially with five classrooms on each floor. In the nineties, the former Israelite school was replaced with an eight-year Lutheran grammar school.

The last section, the fourth direction of development of modernism in Košice is functionalism with a national character. Unlike the international one, this direction has the features of artistic interspersions, which, in our opinion, come from local traditions. Therefore, this functionalism can be called Slovak or even Košice.

However, it still carries a stylized order system of classicism: a distinguished plinth and cornice, window frames and distinguished door portals, stylized colonnades, gabled roofs, and the general subordination of the symmetry of individual parts. Not two, but three main colours are used, as well as three textures – brickwork, polished stone, and concrete. The corner of Moyzesova and Poštova streets looks dynamic and most expressive, and at the same time, the facade from Kuzmány Street, which is quite wide, is not at all expressive.

Generally, the Post Office complex looks like a typical building for Košice.

The State Secondary Grammar School for Girls by Petr Kropáček (1928)

The Purist building manifests not only its stylistic perfection and organic installation into the historic environment but also is an example of the new hygiene trends. As the Czech architect and critic Oldřich Starý stated, the key features of modernist architecture in terms of hygiene were air, light, cleansing, airing, heating, and artificial lighting. Kropáček, like other Czech and Slovak young architects, adopted the principles of the Purist Manifesto of Le Corbusier and Amédée Ozenfant, declaring that “a work of art should induce a sensation of a mathematical order."

At first glance, this building differs sharply from the main one of the city school, which occupies the entire block and was built in the historicist style in 1892–1896. But in fact, this new building is subordinate to the style of the main one. It is also decided in two colours, in the same two textures – red brick and light-plastered planes. Facades are emphasized by horizontal eaves: common and on individual windows or several blocked windows. The necessary details to match the decoration of the old building are added by the lattices of the blinds in the lower part of the vertical corner case.

The house in Fejova Street 3 was built by Ľudovít Oelschläger, like the two neighbouring ones.

The architect presented three different styles. The warehouse on the left is a reconstruction of the building that remained from the time of the fortress. We considered the house on the right as an example of strong local influences on modernism. But this three-story house is closest to functionalism. However, we included it in this section due to the nuanced local influences. As in the case of the State Secondary Grammar School for Girls by Kropáček, the architect tried to preserve the compositional unity of the building, using the decoration in the form of fake rustication (lines of rows of bricks or stone). The entrance is emphasized by a Bauhaus round window, and the roof was sloped (although it probably became that way later).

The residential building at 6 Mojmírova Street, as the previous example, is completely functionalist, but it is supplemented with elements of the decoration, which are quite characteristic of Czechoslovak functionalism. It is a multiple duplication of the over-door cornice with the rounded corners, imitating blinds, it is a design of balcony fences, a small fluted surface (vertical notches) of foundation stones, and complex panels of doors.

In the end, although Košice functionalism has examples of the pure style a-la Le Corbusier, it did not gain popularity here in the interwar period. Evidently, local customers demanded features of individuality, which makes Košice modernism unique. Similar processes took place in almost all European cities. In the architects' theorizing about the cosmopolitan future of architecture, there will always be in practice the customer's desire to stand out from the rest. This individuality can be subtle, can be expressed in one element, and in the design of large neighbourhoods, even in the planning structure, which will be related to the terrain, the prevailing wind direction, etc. However, this difference manifested itself providing the above uniqueness.

List of the sources:

Adriana Priatkova, Jan Sekan.The Urban Planning of Košice and the Development of a 20th Century Avenue // A + U-Architecture and Urbanism. – November, 2020

Adriana Priatková, Peter Pásztor. Architekt Oelschläger – Őry. – Kosice, 2012

Zoznam kultúrnych pamiatok v Košiciach – mestskej časti Staré Mesto (Stredné Mesto)

Register modernej architektúry (Kosice)

Michał Burdziński. Young Slovakia. About the Meanders of Modern Art Between Žilina and Košice

Varechová, Zuzana. Qualitative transformations of housing in Košice in the period of modernism and functionalism

Julia Secklehner. Košice Modernism: Catalogue Review

The research took place as part of the KAIR Kosice Artist in Residence, October - December, 2023